ASHER LIFTIN: KNIGHT’S MOVE

Nino Mier Gallery is delighted to present Knight’s Move, Asher Liftin’s second exhibition with the gallery, and his first presentation in Brussels.

November 8 – December 21, 2024

In this new body of work, comprised of paintings and works on paper, Liftin continues to explore ideas of perception, the constructed image and abstracted realism, frequently adopting the still life to represent the act of seeing. The subjects that Liftin chooses to paint, print and draw, along with the manner in which they are rendered, are mediated—screened, we might say—through an array of art-historical reference.

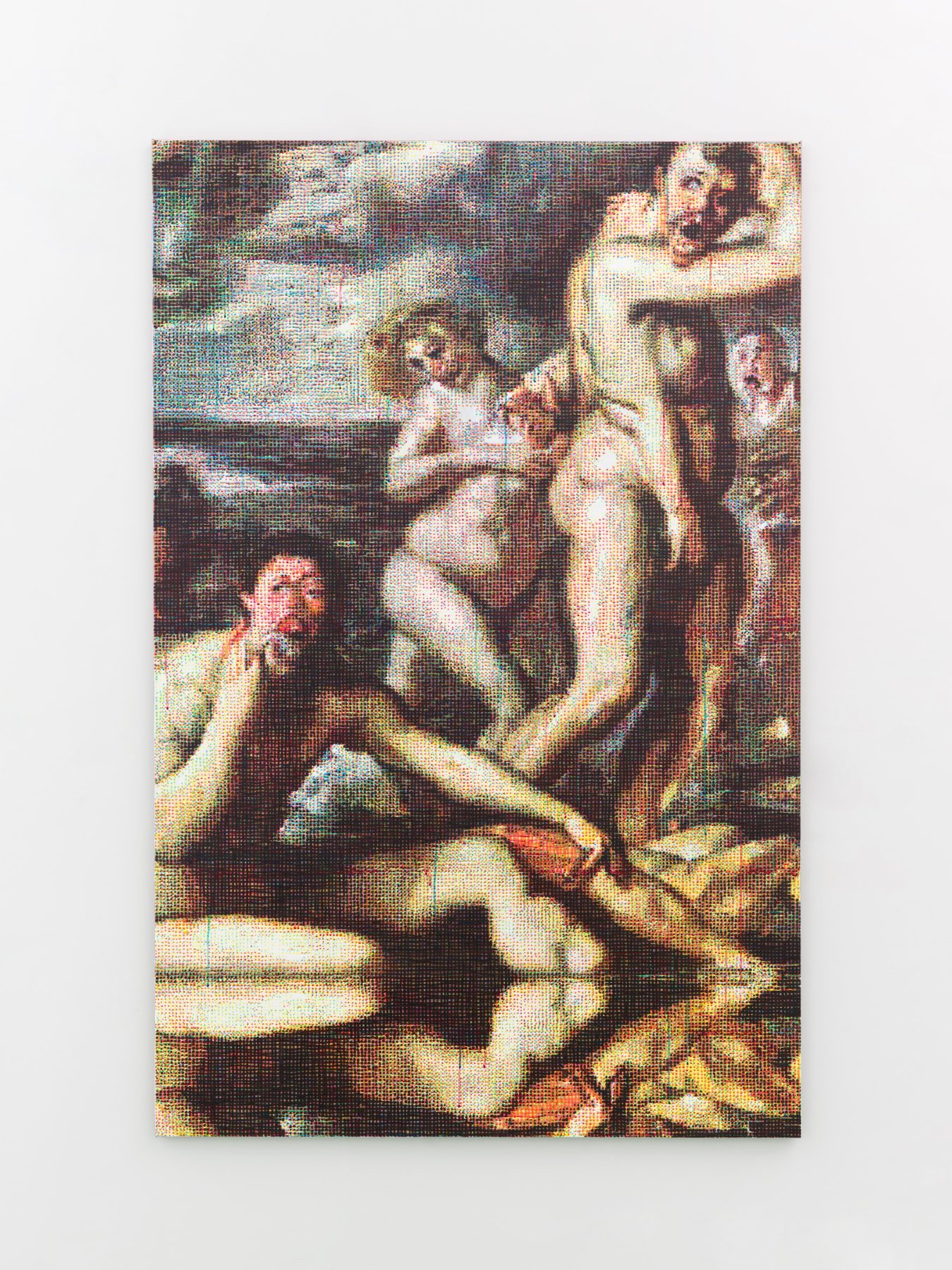

First, still life—flower painting, in particular—reminiscent, for me at least, of Edouard Manet’s poignantly simple “last flowers.” (There is also a lovely little drawing of lemons that reminds me irresistibly of Manet’s own late lemon and other single and double pieces of fruit.) Studio and gallery windows, printed and painted, larger and smaller, which call to mind both the modernist grid and the Italian Renaissance model of the picture-as-window, an opening onto the world on the other side of its notionally transparent surface. Small colored-pencil drawings of a female intimate, at once clearly posed and snapshot-like: these portraits evoke the photo-filtered paintings of Gerhard Richter, as does the topic of the lit candle found in certain drawings and paintings, such as the one mentioned above. Mannerist bathers, culled randomly, by means of a self-censoring prompt given to an AI program, from 17th-century Italian sources such as the work of the so-called “Il Passignano.”

Collaged and swirled paintings that vaguely recall Picasso and Van Gogh. The illusionist gambits of 2oth-century Photorealism and of earlier camera obscura painters such as Johannes Vermeer. And through it all, of course, runs the Neo-Impressionist mark of Georges Seurat, and the divisionist color theory that goes with it. Though it is possible to see Liftin’s paintings as connecting the dots between Vermeer and Richter, however, this screening through the sieve of art history does not really yield any secure time-line; quite the contrary. But it does knit together the threads of a mediated vision, in which the image bank of painting and its sister media is imbricated with cognitive process. Asher Liftin is not a neuroscientist, and this is not “neuro-art-history,” but his is a practice that everywhere invokes the intersection between art and cognition.

Back up from the surface, and ta-da!, it comes into focus. Move in close, and it comes undone. Move away once more and it all comes back together. But move from side to side in front of this joined pair of paintings, and you see it do both, in concert and in oscillating alternation, over and over again.