PETER SAUL: ART HISTORY IS WRONG

© Peter Saul

Peter Saul: Figuration as Rebellion, or the Mad Side of America.

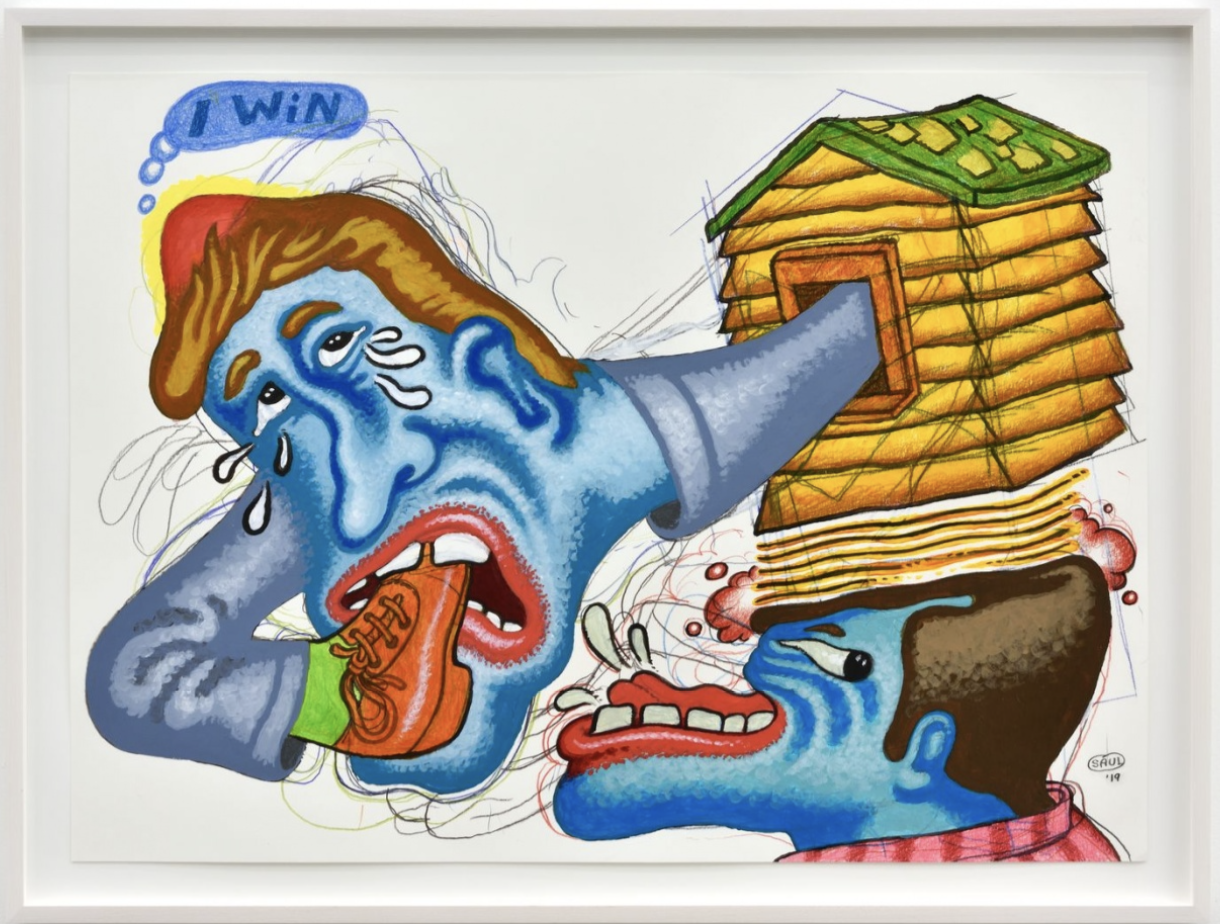

There’s a lot going on in Peter Saul’s paintings: works by the American artist feature vulgar jokes in lush colors, refrigerators and Ronald Reagan, Yankee trash and rich dogs, Superman on the toilet, BANZAI, Mickey Mouse attacking the “Japs,” a “MadDocter” conspiring evil plans. He lavishly presents us the world as a chaotic mess.

Beginning in the late 1950s Peter Saul developed a crossover of pop art, surrealism, abstract expressionism, Chicago imagism, San Francisco funk, and cartoon culture in a language all his own. Peter Saul spent his early formative years near Amsterdam, later moving on to Paris and Rome before returning to San Francisco in 1964. At home in America, he had dreamt of a bohemian lifestyle in Paris: he would just stroll around the city smoking one Gauloise after another. Like Jean Seberg in Godard’s Breathless, he started out by selling the International Herald Tribune on the street. But in Paris, the world’s art capital at the time, he saw the possibility of starting a professional career as an artist. Saul sought out contact with the Chilean painter Roberto Matta, feeling a certain affinity for his work, and the unlikely took place: Matta established put Saul in contact with the Chicago art dealer Alan Frumkin, who would then represent him for many years. Saul also exhibited his work in Paris itself: at Galerie Denise Breteau, and so his career took off in the French capital.

This distance to American culture focused Peter Saul’s artistic gaze: “I definitely wanted to be an outsider and a rebel,” as he puts it in retrospect [1]. Insolent in the best sense of the term, in the mid-1950s he turned to phenomena of mass and consumer culture. Beyond the major schools, Peter Saul developed a highly idiosyncratic painterly oeuvre that escapes simple categorizations. Never actually belonging to a group or a movement, Saul painted in his very own way contrary to changing fashions. Often Saul’s paintings are considered pop art —and there are several arguments for that. Peter Saul shares with pop art an interest in the banal, in consumer society, in the jovial visual worlds of the comics with their glowing, alluring colors. But his work also sets itself apart from pop art. The shock is still palpable when Saul reports of his first encounter with the new art movement in a journal that his American gallerist sent to Paris. Saul’s early paintings in particular, with their preference for a complex-chaotic visual structure that he maintains throughout his career, also shows a certain proximity to the dynamic gesture of the abstract expressionism of an artist like Willem de Kooning, to whom he dedicates an entire series of paintings later on. Peter Saul’s painting combines these contrary systems. In this way, he adds the charm of abstraction to his painting. But there’s a third element as well: there’s increasingly a narrative component, the telling of stories.

At the center of his early work group the Ice Box Paintings, Peter Saul placed a refrigerator as a symbol for affluence and economic growth. Saul’s ice boxes are the antithesis of a prim post-war period. Fittingly, Roland Barthes comments in his Mythologies: “The entire paradise of devices in Elle or L’Express celebrates the closure of the home, its boring introversion, everything that occupies it, infantilizes it, and makes it innocent and severs it from a greater social responsibility [2].” Saul’s ice boxes are like Pandora’s box: there is no well-ordered stock of groceries to be found here. The refrigerator instead gushes with a cacophony of commodities, brands, and wildly painted shapes. Furthermore, the ice box also offers a stage for small episodes and dramas. In one painting, a small green figure dreams in front of the open refrigerator door with all its temptations of a different promise of advertising, flying: up, up, and away?

© Peter Saul

Superman, Superdog, Mickey Mouse, or Donald Duck are figures that truly everybody knows. They are the lowest common denominator of American mass culture: “The objective profile of the United States, then, may be traced throughout Disneyland,” Jean Baudrillard once stated [3]. All values are exaggerated by the comic strip, embalmed and packed up peacefully. This is why this world is a “digest of the American way of life.” But it conceals a deceptive aspect: “Disneyland is there to conceal the fact that it is the ‘real’ country, all of ‘real’ America, which is Disneyland [4].” Donald Duck as an anarchic klutz stands for the average American, just like the morally superior Mickey Mouse. Peter Saul makes them heroes of his stories. But Saul shows us the abysses of the shiny, new, healthy world of popular culture. His figures are broken, comically small and human. We experience Superman, the irreproachable defender of truth and justice, only in his dark moments of defeat. In an entire series of paintings, Peter Saul refers to the reverse side, the bad guys, gangsters, and villains. A Killer (1964) does his dastardly deeds, just like the Super Crime Team (1961/62). Where it all could end is shown in Man in Electric Chair (1964). If the pictures weren’t so colorful, they could be considered pop art’s black series.

In the mid-1960s, Peter Saul’s interest in linking his art to political messages increased. Here as well, at issue is the extreme topicality and closeness of art to life. His art is not elitist nor exclusive, like the modernist avant-gardes. “I just had to look at the newspaper and there it was, the mad side of America,” Peter Saul once said in an interview. The prim America of the 1950s had in the meantime been taken to extremes. The Cold War culminated in the hot war in Vietnam: an ever more powerful counter-culture resisted the anti-communism of the McCarthy era. With great passion, the counter culture despised the demands of consumerist madness, hypocrisy, and the prudishness, vulgarity, and injustice of the world. The counter culture rubbed against the surface of a society that constantly kept a lid on seething conflicts and hardly engaged with problems like anti-democratic tendencies or the militarization of the state. In Alan Ginsberg’s famous harangue against his home country, he wrote furiously: “America, I’ve given you all and now I’m nothing . . . Go fuck yourself with your atom bomb . . . I’m sick of your insane demands [5].” In his own raging against the American reality, Peter Saul’s work meets the holy ire of the Beat generation: William Burroughs, Jack Kerouac or Allen Ginsberg. He creates a furious beat painting when he deals with the dark side of the American dream. Épater le bourgeois: in a rebellious and polarizing way, he painted against the mainstream.

In 1965, Saul was one of the first painters to deal with one of the darkest chapters of American history in this Vietnam paintings. Pictures like Yankee Garbage (1966), Vietnam (1966) or Saigon (1967) emerged as bitter social commentary on the immediate present. These works paradoxically present the simultaneity of excessive humor and playful, but harsh systemic critique, the adjacency of comic-like visual language and garish colors with serious content or even messages. Once again, there’s fiery rage, in this case against the crimes committed by the Americans in the Vietnam War, serves as a motor behind Peter Saul’s painting. All of these paintings are unmistakably biased; they want to take sides. They are also bawdy commentaries on clichéd notions of race and gender used to depict the obscenity of war.

On the pop surface, Saul’s paintings seem initially lurid, seductive, and colorful, but address deeply human and complex issues of American reality: the Vietnam War, race conflict, the gap between rich and poor in American society. “Shocking means talking,” Saul comments on his method. He defiantly pursues his vision of socially-critical pop art until today. The civil rights icon Angela Davis is the subject of several of Saul’s paintings. He has the ultra-conservative Californian governor Ronald Reagan step up to a showdown against Martin Luther King. The former Western hero Reagan, who, in the invasion of Grenada, defended American economic interests, encounters us once again as a dark anti-superman shooting up everything around him. He also presents George W. Bush in Abu Ghraib. Today, these figures have been replaced by Donald Trump.

“I’m doing some damage to ‘good taste,’ but that’s a good thing,” Peter Saul once wrote in a programmatic letter to his gallerist Allan Frumkin [6]. Robert Storr called it fittingly “a stink bomb deposited at the door of the temple of high art [7].” Humor and excess are the weapons that Peter Saul insolently uses in his work. Years later, this became a central strategy of contemporary art under the label “bad painting.” This transgression of all limits has made a great deal possible in art. Long before “bad painting” became a central goal of contemporary art, Peter Saul consciously violated the dictates of good taste. Visionary and with stylistic originality, Saul anticipated the late work of Philipp Guston and influenced a younger generation of American artists. Of great importance for artists such as Mike Kelley, Eric Fischl, Raymond Pettibon, Erik Parker or KAWS, as well as for Nicole Eisenman, Peter Saul is an “artist’s artist,” whose importance could only be presented to a broader audience in recent years.

Peter Saul’s paintings tell stories and they tend towards exaggeration: this is probably the most inclusive way of describing Peter Saul’s opulent work. As an enemy of political correctness and good taste, Peter Saul gives us an oeuvre that is a powerful rampage against the rules of how a modern work of art should be.

Martina Weinhart.

1.“Martina Weinhart im Gespräch mit Peter Saul, Germantown, New York, Juni 2016,” in: Peter Saul, ed. Martina Weinhart (Cologne, 2017), 121.

2. Roland Barthes, Mythologies (Paris, 1957), e-book version, position 745 (translation BC).

3. Jean Baudrillard, “Simulacra and Simulations,” trans. Paul Foss, Paul Patton, and Philip Beitchman, in Jean Baudrillard: Selected Writings, ed. Marc Poster (Stanford, 1988),171.

4. Ibid., 172.

5. Alan Ginsberg, “America,” available online: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/49305/america-56d22b41f119f (last accessed: November 11, 2019)

6. “Peter Saul in Conversation with KAWS,” Peter Saul. From Pop to Punk: Paintings from the 60s and 70s (New York, 2015), 9.

7. Robert Storr, “The Peter Principle,” Peter Saul (Paris, 1999), 16.