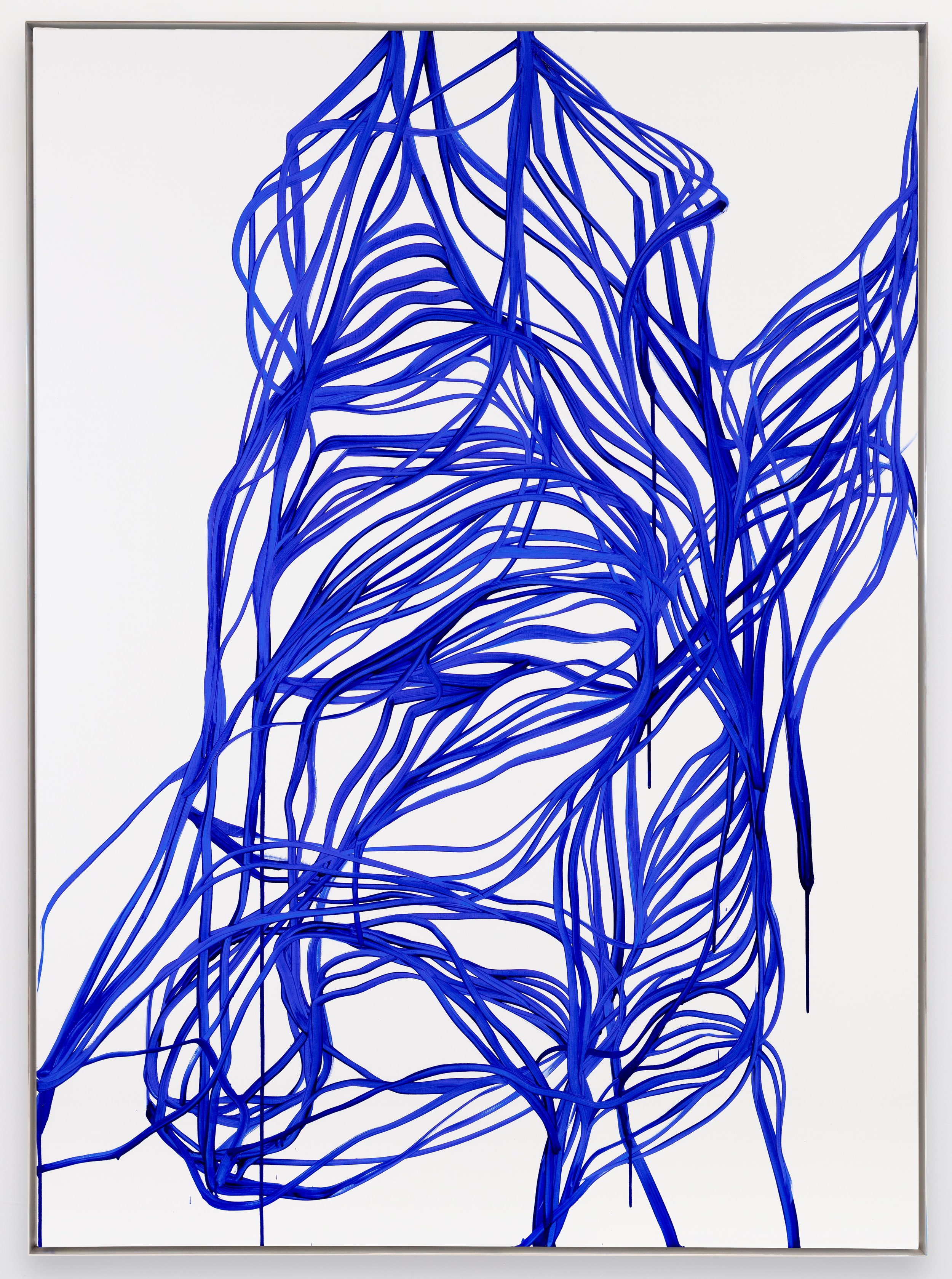

TANYA LING - INTERVIEW

We are pleased to present a written interview with Tanya Ling, a British artist of Indian descent, born in Calcutta in 1966. Ling has built a multifaceted career spanning both fine art and fashion. After studying at Central Saint Martins in London, she worked as a designer for Christian Lacroix in Paris before transitioning into painting, sculpture, and drawing. Her work is deeply rooted in movement, line, and form, and in 2011, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London acquired over fifty of her drawings. Ling’s practice continues to evolve through collaborations and exhibitions worldwide. In this interview, we explore her artistic journey, creative process, and the inspirations behind her most recent works.

1. Artistic Beginnings

After studying at Central Saint Martins and working in the fashion industry in Paris, what led you to transition into fine art? How did these early experiences influence your artistic approach?

I returned from Paris to London because I was pregnant with Pelé, my second child whose father is my husband William Ling. At that time, 1992, William had started a gallery, Bipasha Ghosh in London that showed a group of artists from the YBA scene that had grown out of the London at schools. By default I became a gallerist. Collectors in London, at that time, were thinly spread amongst a growing group of dealers who were a little better resourced and smarter than we were. The gallery was short-lived. William returned to life as an art teacher and I returned to life as a mother and home keeper. My creative life was limited to making drawings on the kitchen table until one of the artists that we had shown, Gavin Turk, let me use his studio to show my drawings. This show was followed by a commission from British Vogue and an unplanned career as a fashion illustrator. I’m not sure how all of this has affected my artistic approach in fact I’m not really sure what my artistic approach is but what I would say is this; for many years I made work to please art directors and now I make work to please art dealers!

2. Creative Process

Your work ranges from fluid line drawings to bold paintings and sculptural pieces. Could you describe your creative process and how you determine which medium best suits your ideas?

Other than the idea that I’m going to make a painting or a sculpture to a film or a drawing with certain materials, I don’t really have ideas. I make work, lost in the moment. It’s as if the work, through the materials finds me, that the work was always there and my job is to find it. I don’t really have a preferred medium. Everything has a unique quality and offers something different.

3. Notable Collaborations

Recently, you collaborated with Feldspar on a collection of hand-painted ceramics. How did this project come about, and what did you take away from the experience?

I can’t quite remember how it happened but we connected through instagram and we did a Zoom call and there was an instant connection. We liked each other and I love what they do and they had warm and generous things to say about my work so we accepted an invitation to visit them in Devon where they have their ceramic studio. Jeremy Brown (one half of Feldspar - the other is his wife Cath), and I started to play around with the clay and Jeremy put it in the kiln , thinking it would break but happily it didn’t so my first bone china sculptures were made. They were shown toward the end of covid in my studio that was then in Covent Garden.

4. Recent Exhibitions

Your exhibition Incitatus at Lyndsey Ingram Gallery introduced a new series of paintings and sculptures inspired by your love of horses and the history of the exhibition space. Could you share the inspiration and development behind this series?

Lyndsey invited me to participate in a group show last year called Language of Line and then offered me a solo show that’s just closed. I had been working in my studio in France where a neighbour visited on a horse. The studio has huge doors and opens out into the field that surrounds it and the horse came in. It was a moment that I wanted to reference. Lyndsey’s new space at 16 Bourdon Street is a former stable so we organised that a horse was present for a pre preview.The word Incitatus derives from a Greek word which has dual meanings; one of which, according to the apostle Peter, means to love one another deeply and the other to the action of a horse at full gallop. It was also the name of Caligula’s favourite horse. Legend has it that the horse lived in a marble stall and ate oats mixed with gold flakes out of an ivory manger.

One of the architectural features of Lyndsey’s gallery, a remnant of the days when the space was a stable, is a strip of green decorative tiles installed at a horse's eye level against which I hung my paintings.. As a child I thought for a while that I was a horse and when I lived in West Africa I had my own horse. I feel a deep connection with horses and it’s an aspiration of mine to paint as if I’m a horse at full gallop. The paintings for my show, VH Farm, in LA with Harper’s were all made in California on a farm that was the home to 19 dressage horses.

5. The Influence of Fashion

Having worked as a fashion designer and launched your own prêt-à-porter collection, how do you think fashion has influenced your art, particularly in terms of color, form, and movement?

I’m not really sure I’m a ‘designer’ or a very good ‘designer’ but my process always started with drawing and I think I struggled to get them from the drawing stage to the finished ready-to-wear stage. There was freedom in the drawings. I called them idea drawings in that they reflected ideas about hair, makeup, colour, clothes and an attitude or a way to be. I guess I want my paintings and sculptures to have at their core a freedom. They are ideas as to what a painting could be and what a painting can do. Fashion has many wonderful qualities but it doesn’t really afford that freedom. There are restrictions inherent in it that I was ill at ease with.

6. Artistic Evolution

Your work has been acquired by major collections, including the Victoria and Albert Museum and Damien Hirst’s Murderme collection. How has your artistic practice evolved since these milestones, and where do you see it heading next?

The V&A acquired a group of fashion drawings that I made 25 years ago for an Elle magazine trend report. Damien Hirst acquired both Line Paintings on paper and sculptures between 2014 and 2017. Since he acquired these works I’ve been fortunate to have worked with Harper Levine in NY who has placed mainly oil paintings on canvas with some great collectors in the US. As for the future I plan to follow my nose and see what happens.

7. Inspirations and Influences

Your work has been acquired by major collections, including the Victoria and Albert Museum and Damien Hirst’s Murderme cYour work often features lines and forms that evoke movement and fluidity. What specific influences or references inform these stylistic choices?

The fashion drawings are, in the main, line drawings. The line is the same as the line in the Line Paintings but the Line Paintings are not figurative and are usually one colour. I’ve recently made a new group of single colour Line Painting in oil on canvas. Lyndsey sold one in the Incitatus show. I’m not sure that it is a question of style. It’s more a question of feeling. They evoke quite powerfully a feeling that collectors have a deep emotional connection to. They transmit messages. There’s a melancholy in the works that people have said also exist in the fashion drawings. I’ve heard that I paint pain. If I do, I like to think there is also hope and strength in them.

8. Advice for Emerging Artists

With a career spanning multiple disciplines and collaborations, what advice would you give to emerging artists looking to develop a unique voice in contemporary art?

There is a temptation to try and become the kind of artist that will be successful and obsess about your imagined place in the art world hierarchy. I guess I struggle with this temptation as much as anyone but one really ought to try to be free of this for the sake of the art and also for the sake of your career. Forgetting about your career in order to have one. It’s a paradox. If you make your living from being an artist and have experienced both feast and famine it’s a difficult act to perfect but it is one that your calling requires of you.